Michael Shrieve

Jazz

Biography

Over the course of his eminent career, Michael Shrieve has written, produced and played on albums that have sold millions of copies worldwide. As the original drummer for Santana, Michael – at age nineteen – was the youngest performer at Woodstock. He helped create the first eight albums of this seminal group, and was on the forefront of shaping a new musical era.

Michael is respected world-wide for his adventurous experimentation with the most creative and masterful musicians. No other drummer has collaborated with such longevity and sophistication alongside artists in such diverse genres as rock, jazz, electronic, DJ and world music. He is well recognized for his groundbreaking adoption of electronic percussion when it was a new medium in the 1970s.

Michael’s recording credits include the masters of popular and avant-garde music – Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones, George Harrison, Pete Townsend, Steve Winwood, Police guitarist Andy Summers, film composer Mark Isham, and such musical luminaries as John Mclaughlin, Stomu Yamash’ta, Klaus Schulze, Freddie Hubbard, Jaco Pastorius, Wayne Horvitz, Bill Frisell, Zakir Hussain, Airto Moriera and Amon Tobin. Many notable publications have cited Michael’s outstanding work: The New York Times, Downbeat, Billboard, Modern Drummer, Musician, Drum, Paris Match, Melody Maker, and Life Magazine.

Michael Shrieve also composes music for film and television. He worked with the director Paul Mazursky on the film, “The Tempest,” and scored music for Curtis Hanson’s “The Bedroom Window,” as well as numerous television movies and shows. In 2002 Michael wrote and produced the song, “Aye Aye Aye,” with Carlos Santana, which appeared on the album, “Shaman.” Rolling Stone magazine acknowledged it as one of the songs that “leaps out of the album, joyful and organic without calculation,” and achieves “globe-spanning euphoria.”

Michael continues to strive for innovative approaches to percussion-based music, and records with both renowned and emerging artists (Skerik, Jack DeJohnette, Zakir Hussain, Reggie Watts), in addition to his own band, Tangletown.

Since 1990, Michael has participated in Seattle’s Bumbershoot Festival as host, performer and curator of the popular “Bumberdrum,” which brings together a stage full of the many percussionists participating in this world-class annual art and music festival. Michael was the Musical Director for the pre-game show of Major League Baseball’s 2001 All Star Game hosted by the Seattle Mariners, which involved over 80 drummers and dancers representing numerous countries.

Michael is the past President of the Pacific Northwest Branch of the National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS), and is currently writing the memoirs of jazz drumming legend Elvin Jones. He serves as Musical Director for Seattle Theater Group’s “More Music @ The Moore,” a program that highlights gifted young musicians from Seattle’s various cultural groups.

Michael Shrieve currently lives in Seattle and Los Angeles. He continues to work on projects that are both groundbreaking and soul-filled. In 2006 he will release a musical collaboration entitled, “Drums of Compassion,” for which he is composer, producer and drummer. It brings together some of the world’s most respected percussionists and musicians: Obo Addy, African Drums; Jack De Johnette, Drums; Jeff Greinke, Keyboards, Sound Sculpture and Composer; Zakir Hussain, Tabla; Airto Moriera, Brazilian Percussion; BC Smith, Orchestral Arrangements; James Whiton, Bass.

Michael Shrieve was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998. In 2005, Michael received the Guitar Center’s first annual “Lifetime Achievement Award.”

“I owe Michael a lot; He’s the one who turned me onto John Coltrane and Miles Davis. I just wanted to play blues until Michael came. He opened my eyes and my ears and my heart to a lot of things. Some drummers only have chops, but Michael Shrieve has vision. Michael is like a box of crayons; he has all the colors.”

Carlos Santana

Michael Shrieve’s Spellbinder is a majestic instrumental band of the first order. The group achieves an unlikely mix of propulsive rock with cool jazz. Only the finest musicianship could allow the sound to coalesce so beautifully into flowing experimentation that is altogether distinctive.

This inspired quintet takes its name from guitarist Gabor Szabo’s tune, which is best known from its brief appearance at the end of Santana’s hit, “Black Magic Woman.” Shrieve’s unit consists of blazing guitarist Danny Godinez, trumpeter Raymond Larsen offering a taste of 70s-era Miles, Hammond B3 organist/magician Joe Doria, and bassist phenom Farko Dosumov—all among the finest of Seattle’s musicians.

Michael Shrieve hopes to take Spellbinder on the road. Playing live nourishes his soul in a different way than does studio recording. As Michael says, “the name Spellbinder reminds me of what my job is: to be a spiritual man who inspires listeners through music, to cast a spell with trance-inducing rhythms that transports listeners to a new place, one that is more free and open.”

Michael Shrieve’s Spellbinder, released in 2016, is the band’s studio recording of original compositions and homages (with trumpet by John Fricke).

Videos

Discography

_No category_

No posts foundYosuke Yamashita Trio

No posts foundSolo Projects

2016

Live at Tost

2008

Micahel Shrieve

with Bill Frisell and Wayne Horvitz

2001

Michael Shrieve

with Jonas Hellborg and Shawn Lane

1996

Shrieve, David Beal with Klaus Schulze & Kevin Shrieve

1989

Michael Shrieve

with Steve Roach

1989

with M. Isham, D.Torn, A. Summers & Terje Gevelt

1989

Compilation

No posts foundCollaboration

No posts foundC. Santana

2016

2002

1975

1974

1974

1974

1973

1973

1972

1971

1970

1969

Music samples

Photos

Press

-

Music Aficionado _ In August of 1969, Michael Shrieve was 20 years old and blowing minds onstage at the Woodstock Festival, playing drums with Santana. The band’s first album wasn’t even out yet. Talk about making a good first impression.

In March of 2016, Michael Shrieve was 66 years old and performing with the newly reunited, Original Santana band at the House Of Blues in Las Vegas. And it’s a safe bet most of the audience there had seen the band’s 1969 performance in the original ‘Woodstock’ film. “I had to study videos and records,” he recalls about this year’s rehearsal sessions, “and I kept saying, ‘My 19-year-old self didn’t make it any easier on my 66-year-old self.’”

So what happened in 46 years?

Lots. Michael Shrieve has been all over the place geographically—San Francisco, New York, London, everywhere else—as well as musically. He has played rock, very visibly, he has played space music, he has played jazz, he has played new age, he has played adventurous electronic music, and he continues to do all of that now. He’s up in Seattle, for the most part, but he’s in plain sight again, for both the remarkably solid Santana IV reunion set of a few months back and the latest album by his own group, Spellbinder.

Shrieve and I recently chatted about the fascinating projects that have peppered his “in between” days since first departing Santana in 1974, and his recent return for the new album. A lot has gone on—and if names like Stomu Yamash’ta, Steve Winwood, Automatic Man and Klaus Schulze mean anything to you, you’ll like what Michael Shrieve has to say.

The initial Santana band broke up in the course of making 1972′s ‘Caravanserai’, but you stayed around for a bit, at least through 1974′s ‘Borboletta’. What were you doing then? Why did you stick around, and why did you leave?

That was exactly that period when after we had the first three albums—the first being the Santana record, the second being Abraxas the third being Santana III—with the spaceman on it—and then a lot of things were happening in our personal lives and in the scene. A lot of drugs were going on, and simultaneously Miles Davis had come out with Bitches Brew and all these other records started happening. And Carlos and I were looking for a new direction. Not just in music, but in a new way to live, because everybody was fucked up. Basically, there were a lot of drugs around the whole scene—I don’t mean just Santana—so both on a personal level and a spiritual level

and a musical level, the thing that seemed most exciting was that stuff that was happening. So we started making a record reflecting the things that we were interested in musically, I think that’s the best way to put it. We wanted a taste of that stuff. And that had a lot to do with the two directions the band went. One direction started Journey, and then Carlos and I continued to do those sorts of explorations.Why did you leave? What was your plan?

I didn’t really have a plan; it just felt like it was time to go. It seemed like at that period of time that Carlos and I, our relationship had played out, and that he wanted more control and was seeing the thing more as his, and prior to that I always felt like we were in it together. And I wasn’t sure where I wanted to go—I thought it’s been a great ride, let me just leave now. I remember going to like a health spa in Baja, California for like a month—and I thought this would be like a good way to leave and then re-enter the world: Just go somewhere, bring your drums, get away from everything, get in a real healthy environment and then come back and think about what you want to do. And what I did was Automatic Man and Go with Stomu Yamash’ta and Steve Winwood.

Tell a bit about how that all happened. You were in San Francisco, but I’d always had the impression those deals were done in the UK.

Yeah, they did get done in the UK. The first thing was, while I was still with Santana, I was looking for Stomu Yamash’ta. I had heard some of his recordings, and I was completely fascinated by this Japanese percussionist. I heard this music and I thought it was otherworldly, I saw this album cover, this gatefold album of his while it was playing at a record store in Berkeley—I looked at it, and here was this crazy Japanese guy with hair all the way down to his back and a stage full of drums and percussion and a tympani stick, leaping in midair. I was like, who the hell is this guy? Finally we met on the last day of a long world tour for Santana, in Rome. I wanted to do avant-garde percussion, and he was moving into a pop thing—and he already had Steve Winwood onboard to so something, and Klaus Schulze, a German synthesist I wasn’t familiar with at the time. So I kind of signed up for that.

But in the meantime, I went back to the Bay Area and started thinking I wanted to do something that was like rock’n'roll—with great playing and great writing—but something that was conceptual and something that was funky, with that rock sound.

So the first person I found was a keyboard player, Bayeté, Todd Cochran—who was kind of a prodigy around the Bay Area and more of a jazz player, but a guy that was also young and listening to Hendrix. One night we went to see Pink Floyd doing The Wall, one of those performances at the Cow Palace, and I remember having a discussion with him, saying, “I’d like to do something conceptual, I’d like to do something thinking big—but the music’s got to be fantastic—it’s rock, but its bigger.” I guess I was looking for some theatrical element or drama. From there we found the guitar player, Pat Thrall, and we went through some bass players, and that’s how that happened. Lou CasaBianca, the manager of the band, knew that I was going over there for Stomu’s Go thing anyway, and I had a connection with (Island Records founder) Chris Blackwell, so he went there, and got a deal with Island. So it worked out that I would go over to do Go, and the guys in Automatic Man would come along and we would live over there—because we wanted to make the record with English rock engineers. So we did it at Olympic Studios, with Chris Kimsey, who later did all the Stones stuff and more. And I did Go there as well, so I was kind of doing double duty in 1976.

Was Go an actual band, or simply a show that came and went?

It was a project of Stomu’s. It was a band—we rehearsed, we did the record, and then we rehearsed for a show at Hammersmith Odeon. He’d already had this avant-garde theater company, so we had lasers and we had these Japanese kabuki sort of characters. So we did that show, and then we did a show in Paris at Palais Des Sports. And that was kind of it for that group. We did the studio album, and then a live album from Paris, and then they went ahead and did a second one. Steve Winwood couldn’t do it, so they brought in different people (including vocalists Jess Roden and Linda Lewis).Tell me about Novo Combo, the rock band.

After London, I moved back to San Francisco and Automatic Man fell apart. I moved to New York in ’79, I think, and I was trying to decide what to do. So I put together a band there called Novo Combo, and we did two albums. That’s one of the things I did—that was a working band, we were trying to get over, that sort of thing. It seems like every time I’d try to put together something commercial, it ends up disastrous, and I’d end up paying money, or losing money, or being sued. Stuff like that. So after Novo Combo, I was sort of, “no more of this.” It seemed to be the universe speaking to me: Just do the music you love. Stop trying to prove to everybody that you can be a commercial success, and just get on with the stuff you love doing. And be happy. Which I did for years. And now I think on my eighth solo project or collaboration.

Tell me a bit about the Novus Records part of your career in the mid-’80s. It was an interesting period when jazz, instrumental, and new age musics were almost intersecting, oddly. How did you feel about that?

I did what I wanted to do. Everything I do seems to fall between the cracks…so it’s not really new age, but it’s electronic, but its got grooves, but not dance grooves like in a club, like EDM would be. I’ve always seemed to fall into the cracks. I worked with a great synthesist in Steve Roach, and I did two records in 1989, one of which was ‘The Leaving Time’ with Steve, and the other one was called Stiletto. That was completely instrumental and certainly jazz influenced—but, you know, it turns out I’m not a jazz drummer. But it was with two guitar players, Andy Summers and David Torn, who are two of my favorites, and I thought it would be interesting to bring them together with Mark Isham, who was a real melodic trumpet player, and this was just when he was getting his film career started. They were both very different records as well, the two of them, and (label founder) Steve Backer from Novus was good enough to let me do them and have a budget.

I also did a record with David Beal then called The Big Picture, and the whole thing was played by drumsticks. Whether it’s strings or horns, drum pads triggered them all. So I consider it a percussion record, although it’s just a music record—and it’s considered kind of new age record, but it’s almost more cinematic in scope than regular new age. There’s a lot of sampling, a lot of triggering of samples, and layered compositions. So that’s that period that you were talking about, which was like the ’80s. I was living in New York at the time, so it was Novo Combo time as well.

I also did a record with David Beal then called The Big Picture, and the whole thing was played by drumsticks. Whether it’s strings or horns, drum pads triggered them all. So I consider it a percussion record, although it’s just a music record—and it’s considered kind of new age record, but it’s almost more cinematic in scope than regular new age. There’s a lot of sampling, a lot of triggering of samples, and layered compositions. So that’s that period that you were talking about, which was like the ’80s. I was living in New York at the time, so it was Novo Combo time as well.I saw a picture of you then in a room chatting with Jeff Beck and Mick Jagger during the making of ‘She’s The Boss’. Were you still maintaining your chops by doing sessions at that time as well?

Yeah—I didn’t get hired a lot to be on people’s sessions. I’m still not. So you just make shit happen, that’s the way I’ve been looking at it for years. You want to do something? Then do it and don’t wait for permission.

With Mick, Mick and I were friends when I was living in NY, and we hung out a lot, and he was doing his record and he was in the Bahamas and just said, I’m working on the record and I think there’s a couple of tracks I think you’d be good for, would you mind coming down? And it was just perfect, because I really wanted to get out of New York City, and I really enjoy Mick. So yeah, it happens to be that Jeff Beck—I mean I didn’t end up on the whole record, but one of the tracks I’m on includes Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend, I think Bill Laswell—we got Michael Henderson down from Miles Davis’s group, Eddie Martinez. It was pretty cool.

In regards to session chops, I always wish people would call me more. They don’t know I can play a backbeat. (laughs)

Tell me about Spellbinder.

I’ve been in Seattle raising two boys that are grown now, and I’ve been playing here. I took up a residency at a club called ToST, and I played there from 5 to 7 years—not always, but for many years, weekly, and I did it just so I’d be playing. I had several bands that I used that space with. One of them was called Tangletown—that was with a vocalist and with two drummers, myself and Kevin Sawka. He played drum ‘n’ bass and EDM stuff. And it was two guitar players and then I made it into a band, but there were too many people—I had horns and everything else.

So with Spellbinder, I wanted to put a band together where I could play drums just like I wanted to play. The older I get, the more I feel like a shaman—like I want to play drums, and I want to affect people a certain way. So this album, Michael Shrieve’s Spellbinder now, it’s the second album—and this is a group that I’d like to take out and tour with, and play with, because they’re great players. We’ve played a lot together, and that’s why I’m trying to get that out there now and create an awareness of it. I had thought this Santana thing would be happening, but it doesn’t seem like we’re touring behind it. Which is very frustrating, but I’d still like to get my ass out there anyway. And Spellbinder I think would be a good way to do that right now.

Any of your recordings seem like they were particularly underrated, that you wish had gotten a wider listening?

I just saw this thing in Rolling Stone on Santana, and the guy made a comment in there that said, “Michael Shrieve’s only claim to fame since Santana was playing percussion on a Mick Jagger record.” And I thought, you motherfucker, you’re going to make my life into some little wipe-ass sentence like that? After doing like eight solo albums, and being more adventurous than most of the guys from my musical generation?” And so I think, if I look at it realistically, I go back and listen to my music and think, “You know what? I still really like it, I like the work I’ve done, you know?” I think that it’s got a certain quality to it, and that I’ve created these different worlds that have quality. I think I should make a sampler or something like that, and just try to create more awareness that it’s cool. The music I make is really cool. Who cares if it’s on the fucking charts?

And now artists can get to their fans more directly than ever before, without the middleman.

Exactly. I have to speak to them, I have to kind of lead people to the water more, that kind of thing. But that’s another story.

-

Interview American Music. On November 4th, legendary drummer Michael Shrieve launched a new show on Jet City Stream called Notes From The Field. Every week, Michael will chat with local and national artists, musicians, chefs, designers and all manner of interesting people to find out what makes them tick.

On January 6th at 9am on Jet City Stream, Michael will speak to his former bandmate and fellow traveler, Carlos Santana. From their first record together to new projects, Michael expanding Carlos’ mind with excursions into Miles and Coltrane, these two Hall Of Famers have HISTORY. How much? Check out a visual tour of their time together:

-

VOICES OF LATIN ROCK. Music ripples from one musician to another, like jungle drums, the architecture of music is disseminated against the current and the music passed on but not over. The true musician is a servant of all he has been and heard and seeks to develop his craft within these walls and also to break down these walls.

-

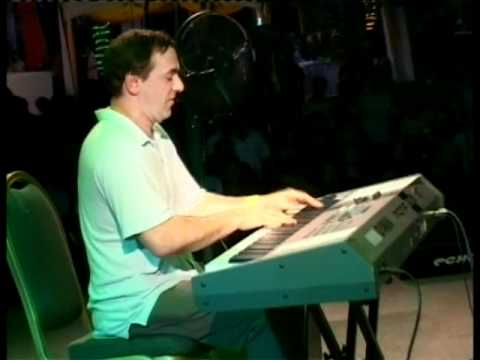

Michael Shrieve’s Spellbinder, an elegant jam band of the first order that mixes rock with jazz in equal and exciting measure. This beautifully conceived quintet takes its name from guitarist Gabor Szabo’s tune, which is best known from its brief appearance at the end of Santana’s hit, “Black Magic Woman.” Shrieve’s unit contains trumpeter John Fricke, offering a taste of 70s-era Miles, organist Joe Doria, guitarist Danny Godinez and bassist Farko Dosumov—all fellow Seattle residents. The band has a standing Monday night gig at the Seattle club Tost, where this exceptionally fine performance was recorded during February 2008.